This had significant implications for the dairy industry where blanket treatment of cows at dry-off with antibiotic Dry Cow Therapy (DCT) was common practice. The alternative and preferred approach is now Selective Treatment (ST) whereby individual cows are assigned Internal Teat Sealant (ITS) or antibiotic treatment according to their Individual Somatic Cell Count (ISCC) and clinical mastitis history. Since the NZVA statement, vets and farmers have embraced, to varying degrees, this and other antimicrobial stewardship initiatives. Amongst those who have resisted the change to selective dry cow therapy, their concerns have included increased risk of mastitis in subsequent lactation and increased Bulk Tank Somatic Cell Count (BTSCC) in the subsequent lactation. But is there any good reason for this inertia?

Vetlife has a relatively large percentage of its dairy clients using ST dry-off policies. Amongst them is the Rangitata Island Dairy Partnership which consists of three farms. The management structure includes an individual manager on each farm overseen by a group supervisor. Each farm milks through a herringbone shed, and herd size varies between the three farms from 600-700 cows (around 2,000 cows in total).

At the 2018 Milk Quality Review, the Partnership supervisors were keen to move towards an ST dry-off strategy using ITS and a short-acting antibiotic DCT + ITS combo. Prior to this they had used blanket long-acting DCT for years. Interestingly at the same time, having used ITS in heifers for several years, they chose to cease that practice as well, feeling they could manage that risk sufficiently through other management options. Vetlife worked with them to implement the change to ST dry-off. Three years later we have looked back at the data to examine how this change in strategy has served each farm, and in particular whether concerns about BTSCC control or mastitis are well-founded.

The change in dry cow therapy policy occurred in the 2018 dry-off season, and so it affected the 2018-19 milking seasons and those thereafter. At that time the policy changed from blanket therapy with a long-acting antibiotic to use of ITS on low cell count cows and combination short-acting DCT plus ITS on cows with high cell count or clinical mastitis occurrences during the season. It was decided to use a lower ISCC cut-off than the generally accepted 250,000SCC/ml because management wanted farm staff to insert the ITS themselves. Reducing the ISCC cut-off reduced the total number of cows receiving only ITS, and it was considered that this would reduce pressure on staff and allow them to concentrate on doing a better and more hygienic job. This new approach was also considered to reduce risk exposure if it failed to deliver the expected outcomes. Vetlife provided on-farm teat sealant insertion training to each farm, and we continue to refresh and reassess this with all staff involved in dry-off each season immediately prior to dry-off on each farm.

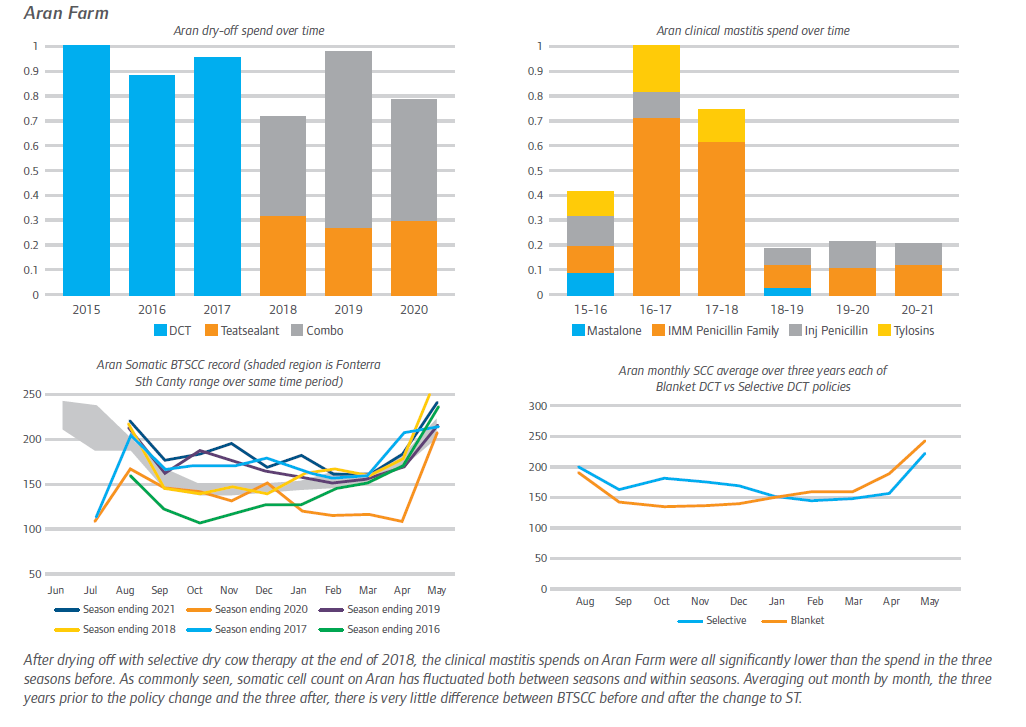

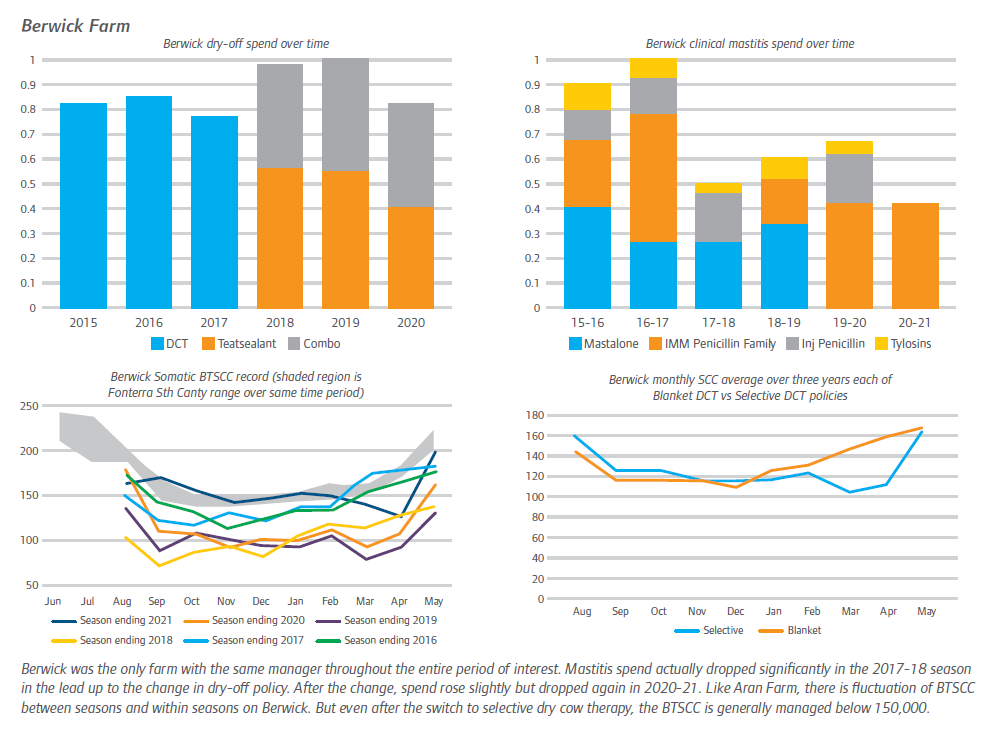

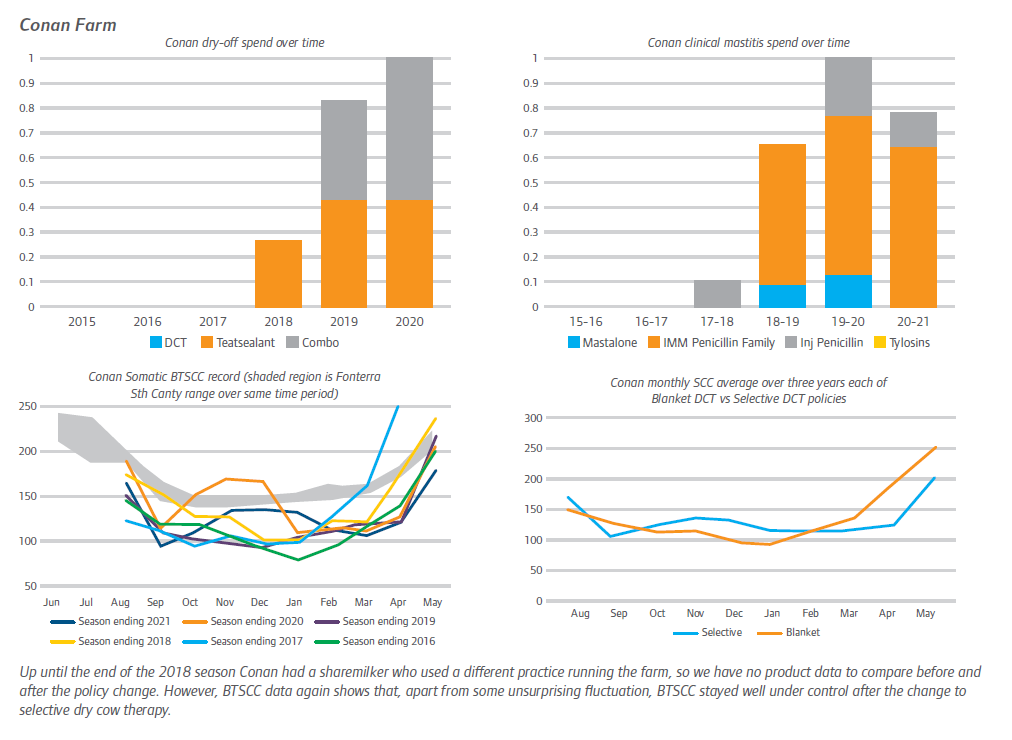

Below are the results from each farm presented in four graphs:

After drying off with selective dry cow therapy at the end of 2018, the clinical mastitis spends on Aran were all significantly lower than the spend in the three seasons before. As commonly seen, somatic cell count on Aran has fluctuated both between seasons and within seasons. Averaging out month by month, the three years prior to the policy change and the three after, there is very little difference between BTSCC before and after the change to ST.

Berwick was the only farm with the same manager throughout the entire period of interest. Mastitis spend actually dropped significantly in the 2017-18 season in the lead up to the change indry-off policy. After the change, spend rose slightly but dropped again in 2020-21. Like Aran farm, there is fluctuation of BTSCC between seasons and within seasons on Berwick. But even after the switch to selective dry cow therapy, the BTSCC is generally managed below 150,000.

Up until the end of the 2018 season Conan had a sharemilker who used a different practice running the farm, so we have no product data to compare before and after the policy change. However, BTSCC data again shows that, apart from some unsurprising fluctuation, BTSCC stayed well under control after the change to selective dry cow therapy.

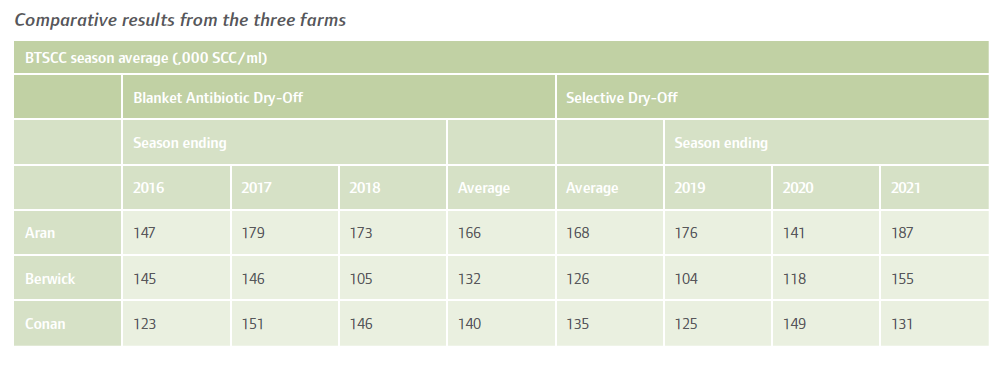

The season average BTSCC does not appear to be greatly affected by the change to selective dry cow therapy.

This data is far from a scientific trial. Various factors influence somatic cell count and clinical mastitis on a farm between different seasons, so there is always some variation. These farms were all affected by the Rangitata flooding in December 2019. They also ceased teat sealing of heifers around 2017 (varied +/- a year between farms). This example does not show anything to suggest that changing to selective dry cow therapy has increased the BTSCC for these farms nor that it has increased the risk of clinical mastitis. Teat sealants and combination therapy should logically reduce early season mastitis and cell count, offering teat protection well past the period of protection offered by even long-acting dry cow antibiotics. It is interesting to note that on these farms the very early season BTSCC is slightly higher after the selective policy was approached, but again this probably should not be overinterpreted.

Based on the experience of these farms, increased BTSCC and increased mastitis risk are not valid reasons to avoid adoption of selective dry cow therapy. Teat sealant can be safely administered to milking cows by farm staff with adequate training and supervision from veterinary clinics. Of course, 250,000SCC/ml ISCC is a somewhat arbitrarily chosen cut-off point. In terms of long-term antibiotic stewardship, there is no reason why a lower figure cannot be chosen to allow a period of proof of concept so that a particular farm management team can become comfortable with the approach. This is far better than simply making no effort to reduce antibiotic use at dry-off. Vetlife continues to make responsible prescribing and judicious use of antibiotics leading principles in its business.

Written by Duncan Crosbie – Vetlife Temuka